Hernias

HERNIAS. COMPLICATIONS OF HERNIAS

A hernia is the protrusion of an organ or the fascia of an organ through the wall of the cavity that normally contains it. A hernia occurs when the contents of a body cavity bulge out of the area where they are normally contained. These contents, usually portions of intestine or abdominal fatty tissue, are enclosed in the thin membrane that naturally lines the inside of the cavity. Although the term hernia can be used for bulges in other areas, it most often is used to describe hernias of the lower torso (abdominal-wall hernias).

HISTORICAL

The early history of interest in hernia is that of the discipline of surgery.

Figure 1. 15th century – Castration modern surgery possible.

The Egyptian papyri do not contain reference to the operative treatment of hernia, but the Papyrus (1552 B.C.) recommended diet and externally applied pressure (truss) for its treatment. The word barbaric is frequently used in terms of surgery during the Middle Century and no less so for the treatment of hernia. Major developments in the knowledge of hernia anatomy and treatment occurred during the eighteenth century.

The nineteenth century brought anesthesia, hemostasis, and antisepsis, which made

As in with wound cauterization or hernia every area of surgery, these sac debridement advances allowed rapid development of the science of hernia surgery (first of all inguinal hernia). Wide acceptance was soon attained in Europe and America for the operation; consisting of ligature and excision of the sac at the external ring and suturing of the pillars around the cord to reduce the size of the ring. This procedure was described in 1877 by Czerny. It is to Marcy of Boston that the modern era of hernial surgery is credited. His understanding of the importance of the transversalis fascia and of the anatomic contribution of fascial repair of the internal ring was reported in 1871. Parenthetically, this was 12 years before Bassini did his first operation for hernia, and 16 years before Bassini published his first paper on the subject.

It remained for Bassini to present a reconstruction technique of the inguinal floor with transposition of the cord. His operation (1884) included high ligation of the sac and reinforcement of the floor of the canal by suturing the conjoined tendon to the inguinal ligament beneath the cord, thus placing the cord under the external oblique aponeurosis. Bassini at this time held the chair of clinical surgery at the University of Padua. Independently and almost simultaneously, Halsted (1852–1922), developed an operation similar to that of Bassini. The Halsted operation (Halsted I) transposed the cord above the external oblique aponeurosis. This procedure was first mentioned in 1889.

Figure 2. Eduardo Bassini – Father of Modern Inguinal Hernia Repair

1. HERNIA: EPIDEMIOLOGY DEFINITIONS

- Latin for “rupture”.

- An abnormal protrusion of an organ or tissue through a defect in its surrounding walls.

- Occur at sites where aponeurosis and fascia are not covered by striated muscle

Epidemiology:

- 700,000 hernia repairs yearly.

- Inguinal hernias –make up 75 % of all hernias.

- 2/3 indirect, remainder are direct hernias.

- Incisional hernias – make up15 to 20 % all hernias.

- Umbilical and epigastric – make up10 % all hernias.

- Femoral – 5 % of all hernias.

- Prevalence of hernias increases with age.

- Most serious complication – strangulation.

- 1 to 3 % of groin hernias.

- Femoral hernias have the highest rate of complications 15 to 20 %.

- It is recommended that all hernias be repaired at the time of discovery.

Hernia is the protrusion of the visceral peritoneum or part of the visceral peritoneum through an abnormal opening. This opening can be natural, for example – Umbilical, Inguinal channel, Femoral ring, Petit’s triangle or can develop after trauma, operations and diseases.

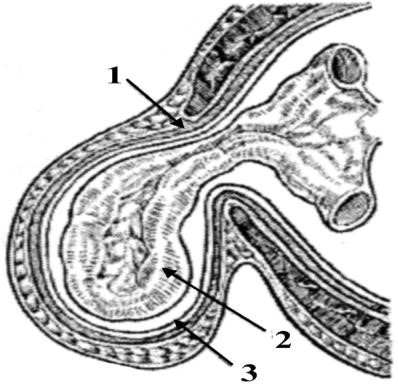

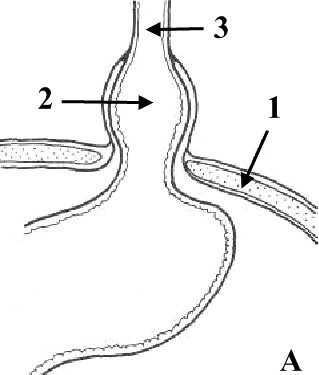

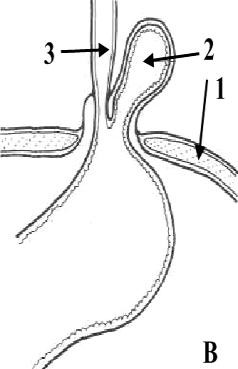

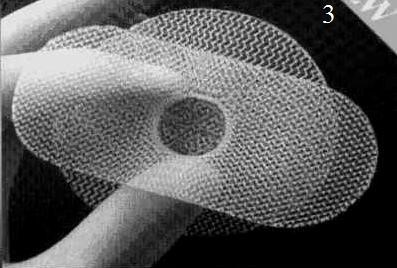

Parts of Hernia: the port (gate), the sac and the contents. The port is the opening in muscle apeneurosis layer. The form of the port can be different; it can be ovoid, ring-like, and triangular and so on. The size of the port can be 20–30 cm. (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Parts of Hernia: 1 – port;

2 – contents; 3 – sac

The sac is part of the parietal peritoneum, which is subdivided into neck, body and top. The sac can be Uni-chamber and Multi-chamber. As usual, the contents of sac can be motile organs of abdomen cavity (loops of small intestine, omentum, transverse colon, sigmoid colon, Uterus e.t.c).

2. ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

The main etiological period of development of hernia is the disturbance of dynamic balance between intra-abdominal pressure and capacity of the abdominal wall to counteract it.

A powerful muscular effort or strain occasioned by lifting a heavy weight, or indeed any condition which raises intra-abdominal pressure, is liable to be followed by a hernia. Whooping cough is a predisposing cause in childhood, while a chronic cough, straining on micturition or on defecation may precipitate a hernia in an adult. It should be remembered that the appearance of a hernia in an adult can be a sign of intra-abdominal malignancy. Premature infants have a high incidence of hernia.

Stretching of the abdominal musculature because of an increase in

contents, as in obesity and in pregnancy, can be another factor. Fat acts as a kind of

“pile-driver” for it separates muscle bundles and layers, weakens aponeuroses, and favors the appearance of paraumbilical, direct inguinal, and hiatus hernias.

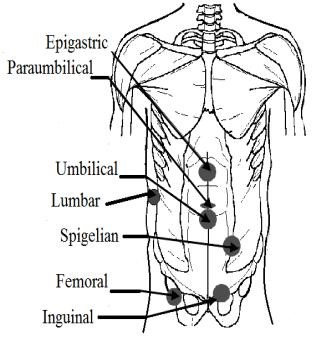

3. LOCALIZATIONS OF HERNIAS

External: the groin (inguinal: indirect and direct; femoral hernia); the middle of the abdomen (epigastric hernia; umbilical hernia; paraumbilical hernia); abdominal wall around a previous incision (ventral hernia); spigelian hernia; lumbar hernia (Petit’s Triangle hernia and Grynfeltt’s hernia); perineal hernia (Fig. 4).

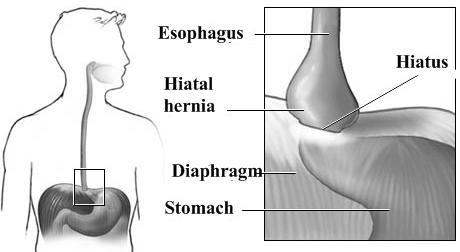

Internal: around the esophagus (hiatal hernia) (Fig. 5); diaphragmatic hernia; obturator hernia; gluteal and sciatic hernias.

Hernia can be: congenial and acquired; reducible (the hernia either reduces itself) and irreducible; sliding; strangulated (obstructed); inflamed.

Figure

4

.

External hernias

Figure

5.

Hiatus hernia:

A

sliding hernia; B

paraesophagus hernia

(1

–

diaphragm, 2

–

hiatus hernia, 3

–

esophagus)

Acute complications: coprostasis; hernia inflammation; strangulated hernia.

Reducible hernia. The hernia either reduces itself when the patient lies down, or can be reduced by the patient or by the surgeon. Note that intestine gurgles on reduction, and the first portion is more difficult to reduce than the last. Omentum is doughy, and the last portion is more difficult to reduce than the first. A reducible hernia imparts an impulse on coughing.

Irreducible hernia. Here the contents cannot be returned to the abdomen and there is no evidence of other complications. It is brought about by adhesions between the sac and its contents or from overcrowding within the sac. Irreducibility without other symptoms is almost diagnostic of an omentocele especially in femoral and umbilical hernia.

Note: any degree of irreducibility predisposes to strangulation.

Sliding hernia. As a result of slipping of the posterior parietal peritoneum on the underlying retroperitoneal structures, the posterior wall of the sac is not formed of peritoneum alone, but by the sigmoid colon and its mesentery on the left, the caecum on the right and, sometimes, on either side by a portion of the bladder. It should be clearly understood that the caecum, appendix, or a portion of the colon wholly within a hernial sac does not constitute a sliding hernia. A small-bowel sliding hernia occurs once in 2 000 cases; a sac less sliding hernia once in 8 000 cases.

A sliding hernia occurs almost exclusively in males. Five out of six sliding hernias are situated on the left side; bilateral sliding hernias are exceedingly rare. The patient is nearly always over 40, the incidence increasing with the weight of years. There are no clinical findings that are pathognomonic of a sliding hernia, but it should be suspected in every large globular inguinal hernia descending well into the scrotum. Large intestine is commonly present in a sliding hernia (or caecum and appendix in a right-sided case).

Occasionally large intestine is strangulated in a sliding hernia; more often nonstrangulated large intestine is present behind the sac containing strangulated small intestine.

Strangulated hernia. A hernia becomes strangulated when the blood supply of its contents is seriously impaired, rendering gangrene imminent. Gangrene may occur as early as 5 or 6 hours after the onset of the first symptoms of strangulation. Although inguinal hernia is four times more common than femoral hernia, a femoral hernia is more likely to strangulate because of the narrowness of the neck of the sac and its rigid walls.

The intestine is obstructed (except in a Richter’s hernia, see below) and in addition its blood supply is constricted. At first only the venous return is impeded. The wall of the intestine becomes congested and bright red, and serous fluid is poured out into the sac. As the congestion increases, the intestine becomes purple in color. As a result of increased intestinal pressure the strangulated loop becomes distended, often to twice its normal diameter. As venous stasis increases, the arterial supply becomes more and more impaired. Blood is extravasated under the serosa (an ecchymosis) and is effused into the lumen. The fluid in the sac becomes bloodstained. The shining serosa becomes dull and covered by a fibrinous, sticky exudate. By this time the walls of the intestine have lost their tone; they are flabby, and are very friable. The lowered vitality of the intestine favors migration of bacteria through the intestinal wall, and the fluid in the sac teems with bacteria. Gangrene appears first at the rings of constriction which become deeply furrowed and grey in color, and then it appears in the antimesenteric border and spreads upwards, the color varying from black to green according to the decomposition of blood in the subserosa. The mesentery involved by strangulation also becomes gangrenous. If the strangulation is unrelieved, perforation of the wall of the intestine occurs, either on the convexity of the loop or at the seat of constriction. Peritonitis spreads from the saс to the peritoneal cavity.

4. CLINICAL FEATURES

Sudden pain, at first situated over the hernia, is followed by generalized abdominal pain, paroxysmal in character and often located mainly at the umbilicus. Vomiting is forcible and usually repeated. The patient may say that the hernia has recently become larger.

Risk factors. When a hernia is not repaired, it may become incarcerated or strangulated. When strangulation occurs, there is a danger that part of the intestine be caught in the hernia cutting off blood supply to the tissue. Also, when a bowel obstruction occurs, it leads to severe pain, vomiting, nausea and inability to have a bowel movement or pass gas. Men are more prompt to suffer inguinal hernias than women, and they risk a damage to their testicles if a hernia becomes strangulated. Also, the pressure caused on the hernia’s surrounding tissues may extend into the scrotum causing pain and swelling.

On examination, the hernia is tense, extremely tender, irreducible and there is no impulse on coughing.

Unless the strangulation is relieved by operation, the paroxysms of pain continue until peristaltic contractions cease with the onset of gangrene when paralytic ileus (often the result of peritonitis) and toxic shock develop. Spontaneous cessation of pain is therefore of grave significance.

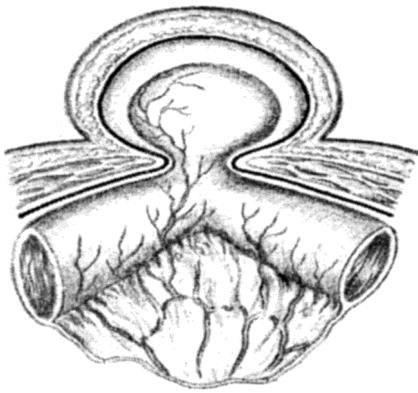

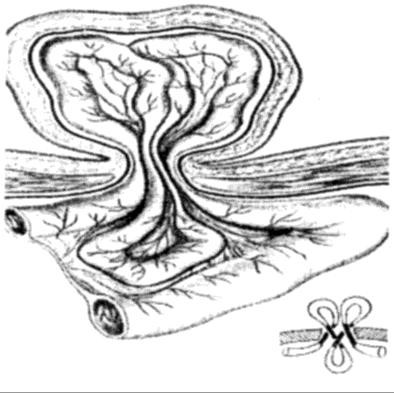

It is necessary to distinguish: typical infringement (elastic and feacal) and atypical (Richter’s hernia, Littre’s hernia, Maidl’s hernia).

Richter’s hernia is a hernia in which the sac contains only a portion of the circumference of the intestine (usually small intestine).

Strangulated Richter’s hernia (Fig. 6) is particularly dangerous as operation is frequently delayed because the strangulated knuckle of bowel is small and there is no obstruction to the bowel lumen. A femoral site is common for this hernia and in a fat woman; the local signs of strangulation are often not obvious. The patient may not vomit, or vomits only once or twice. Intestinal colic occurs, but the bowels are often opened normally or there may be diarrhea; absolute constipation is delayed until paralytic ileus supervenes. Peritonitis often occurs before operation is undertaken.

The Maidl’s hernia is seldom met (Fig. 7).In this form of hernia, hernial ring is restrained not only by mesentery; a loop being in a hernial bag, but, that is especially dangerous, mesenteric gut which is in the abdominal cavity.

Figure 6. Richter’s hernia Figure 7. Maidl’s hernia

Littre’s hernia contains Meckel’s diverticulum.

Inflamed hernia. Inflammation can occur from irritation or sepsis of the contents within the sac, e.g. acute appendicitis or salpingitis, also from external causes, e.g. from a sore caused by an ill-fitting truss. The hernia is tender but not tense, and the overlying skin becomes red and oedematous. Operation is necessary to deal with the cause.

EXTERNAL ABDOMINAL HERNIA

5. INGUINAL HERNIA

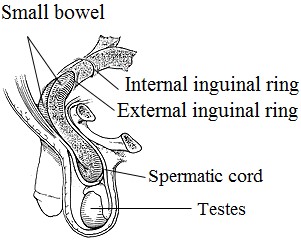

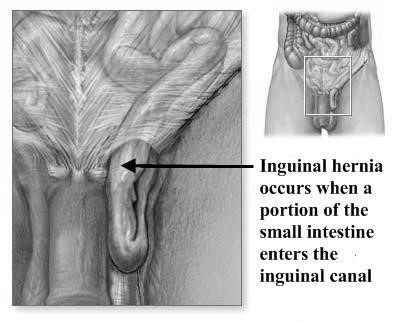

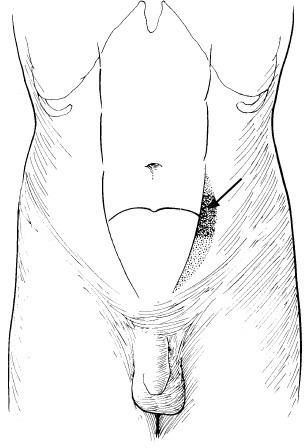

Indirect inguinal hernia. An indirect hernia follows the pathway that the testicles made during fetal development, descending from the abdomen into the scrotum (Fig. 8). This pathway normally closes before birth but may remain a possible site for a hernia in later life. Sometimes the hernia sac may protrude into the scrotum. An indirect inguinal hernia may occur at any age.

Direct inguinal hernia. The direct inguinal hernia occurs slightly to the inside of the site of the indirect hernia, in an area where the abdominal wall is naturally slightly thinner. It rarely will protrude into the scrotum. Unlike the indirect hernia, which can occur at any age, the direct hernia tends to occur in the middle-aged and elderly because their abdominal walls weaken as they age. Figure 8. Inguinal hernia

Direct inguinal hernia. The direct inguinal hernia occurs slightly to the inside of the site of the indirect hernia, in an area where the abdominal wall is naturally slightly thinner. It rarely will protrude into the scrotum. Unlike the indirect hernia, which can occur at any age, the direct hernia tends to occur in the middle-aged and elderly because their abdominal walls weaken as they age. Figure 8. Inguinal hernia

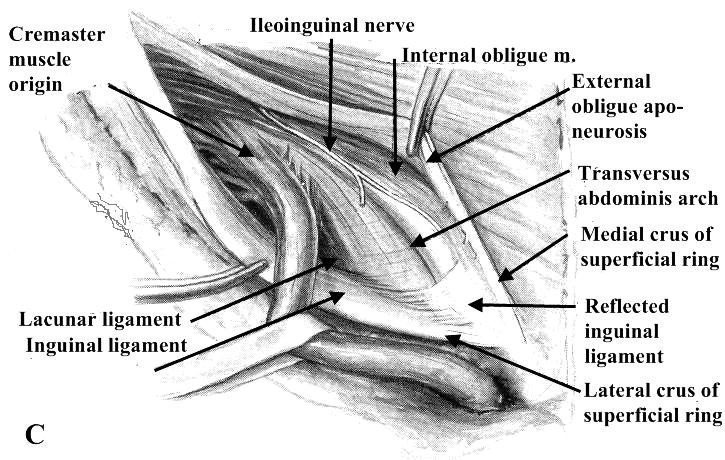

The inguinal canal, which is a tubular opening through the lower part of the abdominal wall, is one of those areas and the region where most hernias occur. In males, this canal contains the spermatic cord; in females, where the canal is not as developed, it contains the uterine round ligament (Fig. 9, 10).

An inguinal hernia can be of the “indirect” or “direct” variety; the

former is most common. Indirect hernias begin at the deep inguinal ring where several abdominal muscles overlap; in these hernias the tissue migrates through the inguinal canal and into the scrotum. In direct hernias the deep inguinal ring is intact, but the tissue protrudes through a weakness in the floor of the inguinal canal above the pubic crest. All types of hernial repair basically involve pushing the tissue back into the abdominal cavity and repairing the defect.

-

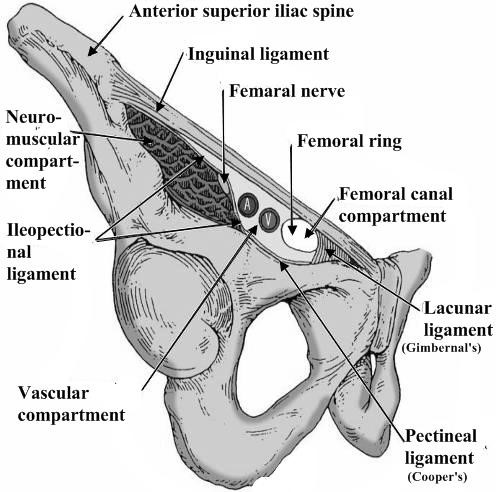

Inguinal ligament (Poupart’s) – inferior edge of external oblique.

Inguinal ligament (Poupart’s) – inferior edge of external oblique. - Lacunar ligament – triangular extension of the inguinal ligament before its insertion upon the pubic tubercle.

- Conjoined tendon (5–10%) – Internal oblique fuses with transversus abdominis aponeurosis.

- Cooper’s Ligament – formed by the periosteum and fascia along the superior ramus of the pubis.

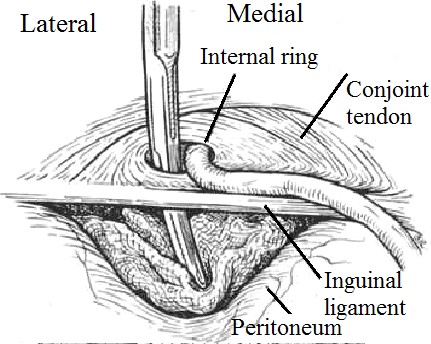

Figure 9. Inguinal canal

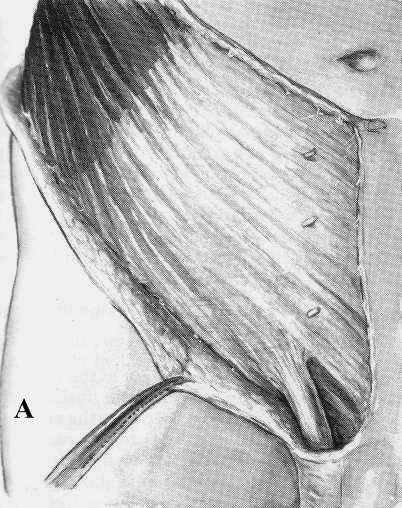

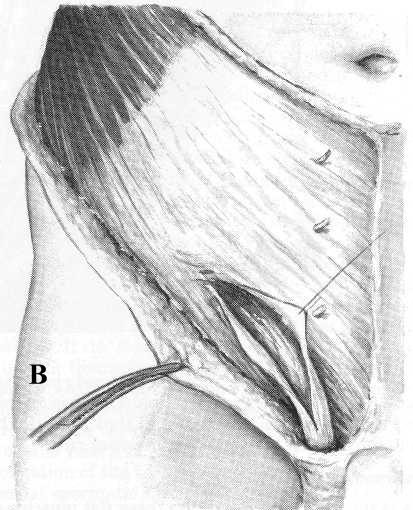

Figure 10. Dissection of the inguinal canal:

- – The intact external oblique lamina is depicted.

- – The external spermatic fascia and innominate fascia have been incised through the superficial inguinal ring.

- – The external oblique aponeurosis has been opened widely and the spermatic cord mobilized by transection of many of its areolar (cremastic fascia) attachments to the walls of the inguinal canal

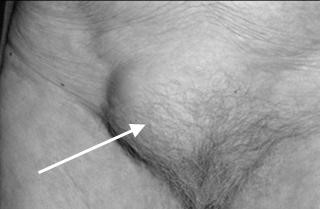

Clinical presentation:

- Groin bulge (Fig. 11, 12, 13, 14).

- Often asymptomatic.

- Dull feeling of discomfort or heaviness in the groin.

- Focal pain – raise suspicion for incarceration or strangulation.

- Symptoms of bowel obstruction.

Figure 11 Male inguinal hernia

Figure 12 Female inguinal hernia

Figure 13. Inguinal hernia (indirect) Figure 14. Inguinal hernia (direct)

The characteristic of indirect inguinal hernia (Fig. 13):

- Is a congenital lesion.

- Occurs when bowel, omentum or other abdominal organs protrudes through the abdominal ring within a patent processus vaginalis.

- If the processus vaginalis does not remain patent an indirect hernia cannot develop.

- Most common type of hernia.

Note: the hernia sac passes outside the boundaries of Hesselbach’s triangle and follows the course of the spermatic cord.

The characteristic of direct inguinal hernia (Fig. 14):

- Proceeds directly through the posterior inguinal wall.

- Direct hernias protrude medial to the inferior epigastric vessels and are not associated with the processus vaginalis.

- They are generally believed to be acquired lesions.

- Usually occur in older males as a result of pressure and tension on the muscles and fascia.

Note: the hernia sac passes directly through Hesselbach’s triangle and may disrupt the floor of the inguinal canal.

Causes of groin hernias: divided into two categories congenital and acquired defects.

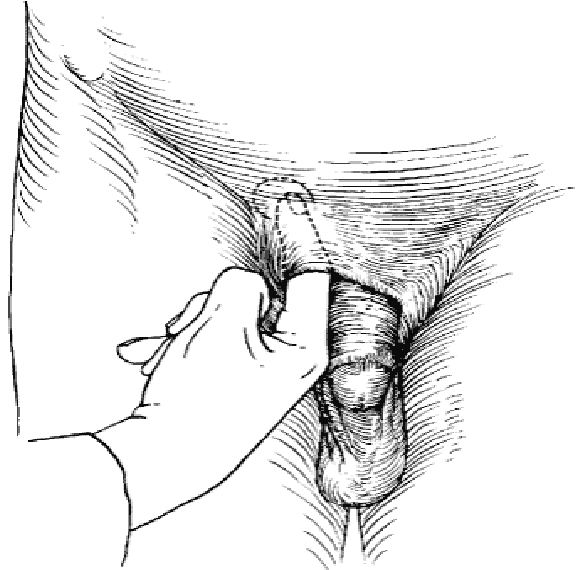

Physical examination:

- The patient should be standing and facing the examiner (Fig. 15).

- Visual inspection may reveal a loss of symmetry in the inguinal area or bulge.

- Having the patient perform valsalva’s maneuver or cough may accentuate the bulge.

- A fingertip is then placed in the inguinal canal; Valsalva maneuver is repeated.

- Differentiation between indirect and direct hernias at the time of examination is not essential. Allows the hernia contents to fill the sac, making the hernia obvious on examination:

Invaginate the scrotum near the external ring and direct the finger medial towards the pubic tubercle. The finger will thus lie on the spermatic cord with the tip of the finger within the external ring. The patient is then asked to cough or perform a Valsalva maneuver. Will be felt as a silk-like sensation against the gloved finger of the examiner… “cough impulse” sign.

Invaginate the scrotum near the external ring and direct the finger medial towards the pubic tubercle. The finger will thus lie on the spermatic cord with the tip of the finger within the external ring. The patient is then asked to cough or perform a Valsalva maneuver. Will be felt as a silk-like sensation against the gloved finger of the examiner… “cough impulse” sign.

The female patient does not

Figure 15. Examine the patient have the long and stretched spermatic in the standing positions cord to follow with the examiner’s

finger during the physical examination. Instead, two fingers can be placed along the inguinal canal, and the patient is asked to cough or strain.

As an oblique inguinal hernia increases in size it becomes more obvious when the patient coughs, and persists until reduced. As time goes on the hernia comes down as soon as the patient assumes the upright position. In large hernias there is a sensation of weight, and dragging on the mesentery may produce epigastric pain. If the contents of the sac are reducible, the inguinal canal will be found to be commodious. During examination surgeon understands: Is the hernia right, or left, or bilateral? Is it an inguinal or a femoral hernia? Is it a direct or an indirect inguinal hernia? Is it reducible or irreducible? (Patient has to lie down for this to be ascertained). What are the contents – bowel, or omentum?

Note: examination using finger and thumb across the neck of the scrotum will help to distinguish between a swelling of inguinal origin and one which is entirely intrascrotal.

Radiologic investigations herniography:

- Suspected hernia, but clinical diagnosis is unclear.

- Procedure done under flouroscopy following injection of contrast medium.

- Frontal and oblique radiographs are taken with and without increased intra-abdominal pressure.

- Ultrasonography.

- MRI.

- CT.

5.1. TREATMENT OF INGUINAL HERNIA

Indications for Operative Repair:

- Early repair is justified when potential for strangulation is weighed against minimal risks for surgery.

- Not warranted in terminally ill without incarceration.

- Patients with ascites should have it controlled before surgery.

- Incarceration, strangulation.

Surgical Techniques:

- Open anterior repair (Bassini, McVay, Shouldice).

- Open posterior repair (Nyhus, preperitoneal).

- Tension-free repair with mesh (Liechtenstein).

- Laparoscopic.

Operative treatment.

Operation is the treatment of choice. It must be remembered that patients who have a bad cough from chronic bronchitis should not necessarily be denied operation, for these are the very people who are in danger of getting a strangulated hernia. As these patients are often elderly, the surgeon should consider giving extra strength to the repair by a synchronous orchidectomy and full closure of the internal ring. In adults, local, epidural or spinal, as well as general anesthesia can be used.

Inguinal herniotomy is the basic operation which entails dissecting out and opening the hernial sac, reducing any contents and then transfixing the neck of the sac and removing the remainder. It is employed either by itself or as the first step in a repair procedure (herniorrhaphy).

Herniotomy and repair (herniorrhapy). This operation consists of (1) excision of the hernial sac (above), plus (2) repair of the stretched internal inguinal ring and the transversalis fascia, and (3) further reinforcement of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. Stages (2) and (3) must be achieved without tension, usually by ‘darning’ with a monofilament suture material such as polypropylene. Fascial flaps, or synthetic mesh implants, are employed when the deficiency of the posterior wall is extensive.

5.2. OPERATIVE PROCEDURES

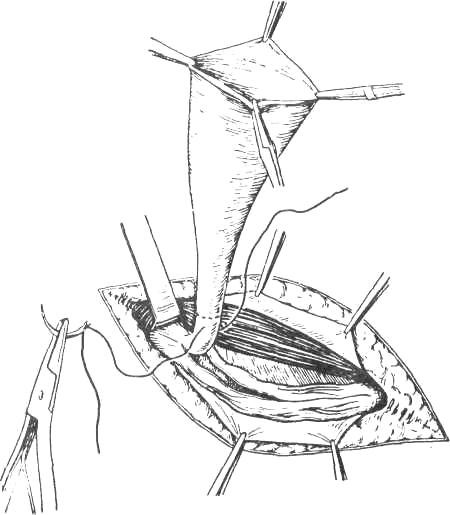

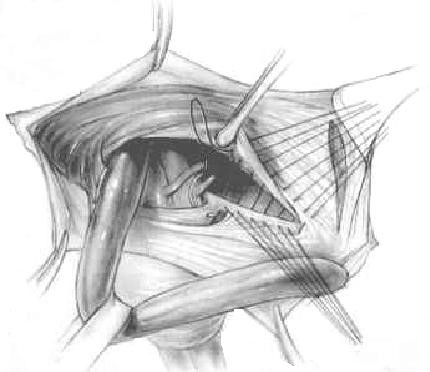

General principles. Excision of the hernial sac (adult herniotomy). Before the skin incision in large inguinoscrotal hernias, the usual antiseptic preparation of the skin should not be extended to the perineal aspect of the scrotum, for, by so doing, severe bacterial contamination of the operation site is likely. The operation approach should be confined to the anterior inguinal and scrotal aspects. An incision is made in the skin and subcutaneous tissues

1.25 cm above and parallel to the medial two-thirds of the inguinal ligament. In large irreducible herniae the incision is extended into the upper part of the scrotum. After dividing the superficial fascia and securing complete haemostasis, the external oblique aponeurosis and the superficial inguinal ring are identified. The external oblique aponeurosis is incised in the line of its fibers, and the structures beneath are carefully separated from its deep surface before completing the incision through the superficial inguinal ring. In this way the ilioinguinal nerve is safeguarded. With the inguinal canal thus opened, the upper leaf of the external oblique aponeurosis is separated by blunt dissection from the internal oblique. The lower leaf is likewise dissected until the inner aspect of the inguinal ligament is seen. The cremasteric muscle fibers are divided longitudinally to open up the subcremasteric space and display the spermatic cord, which is then lifted out.

Excision of the sac. The indirect sac is easily distinguished as a pearly white structure lying on the upper side of the cord and, when the internal spermatic fascia has been incised longitudinally, it can be dissected out and then opened between haemostats.

Variations in dissection. If the sac is small (e.g. bubonocele) it can be freed in toto. If it is of the long funicular or scrotal type, or is extremely thickened and adherent, the fundus need not be sought. The sac is freed and divided in the inguinal canal. Care must be taken to avoid damage to the vas deferens and the spermatic artery, including the blood supply to the epididymis.

An adherent sac can be separated from the cord by first injecting saline under the posterior wall from within. A similar tactic is used when dissecting the gossamer sac of infants and children.

Reduction of contents. Intestine or omentum is returned to the peritoneal cavity. Omentum is often adherent to neck or fundus of the sac; if to the neck, it is freed, and if to the fundus of a large sac, it may be transfixed, ligated and cut across at a suiTable site. The distal part of omentum, like the distal part of a large scrotal sac, can be left in situ (the fundus should not, however, be ligated).

Whatever type of sac is encountered, it is necessary to free its neck by blunt and gauze dissection until the parietal peritoneum can be seen on all sides. Only when the extraperitoneal fat is encountered and the inferior epigastric vessels are seen on the medial side has the dissection reached the required limit. If it has not been done already, the sac is opened. The finger is passed through the mouth of the sac in order to make sure that no bowel or omentum is adherent. The neck of the sac is transfixed and ligated as high as possible, and the sac is excised 1.25 cm below the ligature (Fig. 16).

Reinforcement of the posterior inguinal wall is achieved by approximating without tension; the tendinous and aponeurotic part of the conjoined muscle to the pubic tubercle and to the undersurface of the inguinal ligament. The suturing method includes a choice between: simple interrupted stitches (Bassini type). After extraction of the hernial sac, the spermatic duct is clamped and held. Sutures are placed between the borders of transverse muscle, internal oblique muscle, transverse fascia and inguinal ligament interrupted. Except that, few sutures are placed between the border of abdominal rectus muscle sheath and pubic bone periosteum. In the way, inguinal space is closed and posterior wall strengthened. Spermatic duct is placed on the new-formed posterior wall of the inguinal canal. Over the spermatic duct the aponeurosis is restored by interrupted sutures.

Figure 16. Isolation and ligation of the neck of the sac

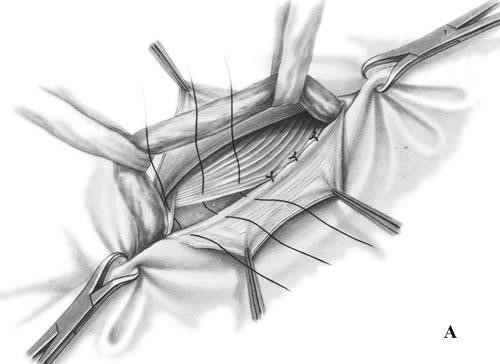

Bassini Repair (early 20th Century):

- Is frequently used for indirect inguinal hernias and small direct hernias.

- The conjoined tendon of the transversus abdominis and the internal oblique muscles is sutured to the inguinal ligament (Fig. 17, A).

- It is sewn up the aponeurosis of external oblique abdominis muscle (Fig. 17, B).

Figure 17. Bassini repair

Bassini’s operation epitomized the essential steps for an ideal tissue repair. He opened the external oblique aponeurosis through the external ring, then resected the cremasteric fascia to expose the spermatic cord. He then divided the canal’s posterior wall to expose the preperitoneal space and did a high dissection and ligation of the peritoneal sac in the iliac fossa. Bassini then reconstructed the canal’s posterior wall in 3 layers. He approximated the medial tissues, including the internal oblique muscle, transversus abdominus muscle and transversalis fascia to the shelving edge of the inguinal ligament with interrupted sutures. He then placed the cord against that newly constructed wall and closed the external oblique aponeurosis over it, thereby restoring the stepdown effect of the canal and reforming the external inguinal ring (Fig. 17).

There have been numerous modifications of Bassini’s original technique, although many of the less detailed renditions have yielded poor results. Those that avoided opening the posterior wall, for example, resulted in suture-line tension between tissues at the most medial part of the inguinal canal just cephalad to the pubic bone. Some help was afforded the Bassini technique and other tissue repairs by the introduction of relaxing incisions by surgeons such as Wolfer, Halsted, Tanner, and McVay.

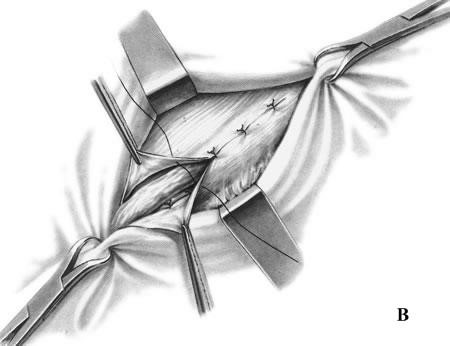

McVay Repair:

- Is for the repair of large inguinal hernias, direct inguinal hernias, recurrent hernias and femoral hernias.

- The conjoined tendon is sutured to Cooper’s ligament from the pubic tubercle laterally (Fig. 18).

Note: this repair reconstructs the inguinal canal without using mesh prosthesis.

McVay and Anson revived Lothiessen’s operation in 1942 (Fig. 18). They considered the superior pubic ligament to be the ideal structure for reconstructing the posterior wall of an inguinal hernia, since it shares the same tissue plane and is derived from the same tissue origin as the transversus

aponeurosis and the transversalis fascia. However, many surgeons who attempted this procedure found that it was sometimes difficult to approximate the transversus arch to the Cooper ligament. Doing so frequently resulted in considerable suture-line tension – enough to require one or more relaxing incisions. Patients complained of considerable and prolonged postoperative pain, and failure rates became unaccep table. This procedure has, however, had value to surgeons by demonstrating

Figure 18. McVay repair

the strength of the superior pubic ligament and showing its utility in large and difficult hernia repairs, including incisional hernias. It is a reliable structure to which prosthetic material can be fixed when a large defect must be spanned.

Shouldice repair. The Shouldice repair (Fig. 19) has been refined over several decades and is the gold standard for the prosthesis-free treatment of inguinal hernias. A recurrence rate around 1 % has been consistently demonstrated over the years. The objective of this paper is to outline and highlight the key principles, including the dedicated pre-operative preparation, the use of local anesthesia, a complete inguinal dissection and the eponymous four-layered reconstruction. A knowledge and understanding of inguinal hernia anatomy and the pathophysiology of recurrence are vital to achieving a long-term success and patient satisfaction for a pure tissue repair.

Figure 19. Shouldice repair

Canadian surgeon E. E. Shouldice contributed substantially to hernia surgery in the second half of the 20th century. He founded a clinic that has since become a hospital devoted exclusively to the treatment of abdominal wall hernias. The Shouldice operation for hernia repair revitalizes Bassini’s original technique. It applies the principle of an imbricated posterior wall closure with continuous monofilament suture. Local anesthesia is routinely used and bilateral hernias are usually repaired separately, 2 days apart. Patients walk to and from the operating room, begin exercise therapy on the day of surgery, and resume their usual activities within a reasonable time after the operation.

An unusual feature of the procedure is the routine sacrifice of the lateral cremasteric bundle, a structure that contains the external spermatic vessels and the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve. Shouldice surgeons have not reported any ill effects related to this step. In fact, before using this technique, pubic tubercle recurrences were unacceptably high. The minor sensation loss that results from dividing that nerve has not proven to be a substantial or longstanding disability. However, when the lateral flap of the cremasteric fascia is sacrificed, ptosis of the testicle will occur. This can be prevented by fixing the distal pedicle of the cremasteric fascia to the external oblique when the canal is restored.

The Shouldice repair has been considered the gold standard of hernia repairs for the last 4 decades, although its use has declined since the introduction of various tension-free prosthetic repairs. The Shouldice repair remains an excellent option, however, and has produced the best and most enduring results of any other pure tissue repair.

Use of prosthetics in hernia repair. The need for a satisfactory prosthesis for hernia repair has been recognized for more than a century. Various materials, including autografts (the patient’s own tissue), have been tried. The most successful of the autografts is fascia lata, which has been used as suture material, a pedicle graft, and as a free transplanted graft. However, in addition to requiring a second operation to harvest it, fascia lata weakens and fails over time and dissolves in the presence of infection.

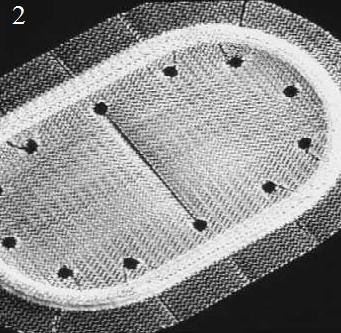

Artificial prostheses. Many authors have attempted to define characteristics of the ideal prosthetic material for hernia repairs (Table 1), although attempts to achieve this “ideal” have met with varying degrees of success (see Tables 2 3). No currently available prosthesis is perfect or free of problems, and the choice of material thus requires compromise. Surgeons do, however, have a large array of products from which to choose.

Table 1 Characteristics of an ideal prosthesis

The ideal prosthetic mesh should:

Not be physically modified by tissue fluids

Be chemically inert

Not excite inflammatory or foreign body reaction

Be noncarcinogenic

Not produce allergy or hypersensitivity

Be capable of resisting mechanical strain

Be capable of being fabricated in the form required, and constructed in a way such that sutures or cutting will not cause the mesh to unravel or fray

Be sterilizable

Be permeable and allow tissue ingrowth within it

Stimulate fibroblastic activity to allow incorporation into tissue rather than sequestration or encapsulation

Be sufficiently pliable so as not to cause stiffness or to be felt by the patient

Strong enough to resist bursting by the maximum forces that can be created by intraabdominal pressure or from an outer force

Table 2 Metal prosthetic graft material

Silver filigree mesh (1900) Became brittle and fractured and eventually extruded causing multiple sinuses and fistulas. Fractured and caused sinus formation.

Toilinox (stainless steel) Set up electrolyte reactions between ingredients if composition varied.

Table 3 Nonmetal synthetic prosthesis

Nylon (1944) Replaced rubber, metals and animal products. Initially used for sutures, later knitted or woven into patches for hernia repair; disintegrates in tissue and loses most of its tensile strength within 6 months.

Polyethylene mesh (1958) High-density polyethylene mesh (Marlex, 1958) resistant Polypropylene mesh (1962) to chemicals and sterilizable, but unraveled after being cut. Modified to polypropylene mesh (1962). Available under

various trade names (Hertra-2, Marlex, PROLENE, Surgipro, Tramex, Trelex). Available as a flat mesh as well as 3-dimensional devices (Altex, Hermesh3, PerFix Plug, PROLENE Hernia System).

Polyester mesh (MERSILENE) Composed of polyester fiber with the characteristics of (1984) filigree; can be inserted into narrow spaces without distortion.

Expanded Teflon product; produces minimal adhesions when placed polytetrafluoroethylene intraperitoneally. Does not allow significant fibroblastic or angiogenic ingrowth; must be removed if infection occurs.

Polyglycolic acid mesh (Dexon) Absorbable mesh; loses strength after 8–12 weeks; Polyglactin 910 mesh (Vicryl) should not be used as a sole prosthesis for the repair of abdominal or groin hernias

Complications related to the use of prosthetics. Materials composed of polypropylene and polyester insight a prompt and strong fibroblastic tissue response with minimal inflammation. This response consists of macrophages and giant cells, most of which eventually disappear. Fibroblastic activity allows rapid integration of the prosthesis into tissues; however, contraction of the enveloping scar tissue creates undesirable deformation of unsecured pieces of the monofilament; its free margins tend to curl, and small pieces roll up. There also have been some reports in the literature of freeform and preformed prosthetic mesh products migrating.

Serum or blood that accumulate in dead spaces surrounding any prosthesis becomes an excellent media for infection. Suction drainage is therefore advisable to eliminate dead space as well as to remove serum collections. Intestinal obstruction and fistula formation are serious complications and often require removal of the mesh/prosthesis. When a prosthesis is placed inside the peritoneal cavity, various degrees of visceral adhesions form depending upon the type of material used. When this is unavoidable, omentum or an absorbable prosthesis should be interposed between the mesh and the bowel.

Treatment of infection involves the application of basic surgical principles. Although most infections occur acutely, delayed infections involving nonabsorbable prostheses can occur months or years later. In the case of an acute infection of a groin hernia repair, it is advisable to quickly and widely open the wound (including the subcutaneous layer down to the external oblique) to avoid chronic sinus formation. A specimen should be taken for culture and sensitivity, irrigation and antibiotics started and healing observed by secondary intention.

Frequent wound check to remove accumulated fluid is advisable.

If a prosthetic mesh had been used in the repair, it can usually be left in place if the above measures are employed promptly. If the wound closes, but a sinus continues to drain, it is likely that the mesh and all old suture material will need to be removed. Unlike early infection, when the mesh can be salvaged, late infection involving mesh requires the complete removal of the unincorporated material, although the incorporated mesh may be left undisturbed.

If the surgeon encounters an inflammatory granuloma in the course of repairing a recurrent inguinal hernia, it is prudent to avoid using a new prosthesis. Gram staining of the inflammatory granuloma at the time of surgery is not sufficiently reliable to exclude subsequent infection. In most cases of persistent infection related to a prior prosthetic repair, the culprit is the nature of the suture material rather than the graft itself. Multifilament and braided sutures, such as silk and cotton should be avoided.

Tension-free hernia repair. The most important advance in hernia surgery has been the development of tension-free repairs. In 1958, Usher described a hernia repair using Marlex mesh. The benefit of that repair he described as being “tension-eliminating” or what we now call “tension-free”. Usher opened the posterior wall and sutured a swatch of Marlex mesh to the undersurface of the medial margin of the defect (which he described as the transversalis fascia and the conjoined tendon) and to the shelving edge of the inguinal ligament. He created tails from the mesh that encircled the spermatic cord and secured them to the inguinal ligament.

Every type of tension-free repair requires a mesh, whether it is done

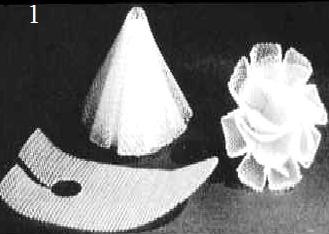

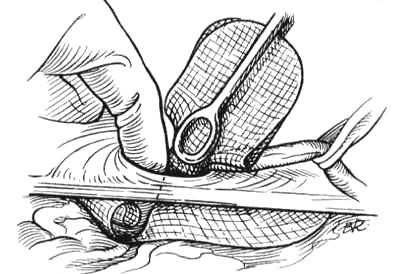

through an open anterior, open posterior, or laparoscopic route. The most common prosthetic open repairs done today are the Kugel patch repair, the Lichtenstein onlay patch repair, the PerFix plug and patch repair, and the Prolene Hernia System bilayer patch repair (Fig. 20, 21).

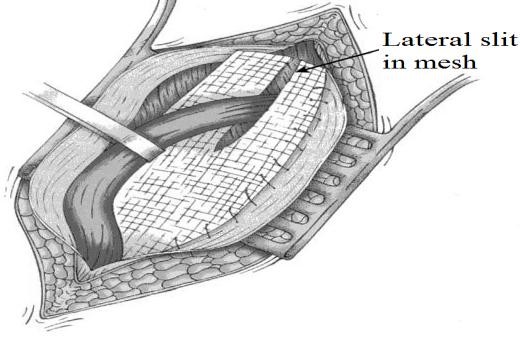

Figure 20. Lichtenstein repair (1989):

Figure 20. Lichtenstein repair (1989):

mesh is sutured from the transversus arch to the shelving edge of the

inguinal ligament creating a “tensionfree” repair

Lichtenstein Repair (1989):

- One of the most commonly performed procedures.

- A mesh patch is sutured over the defect with a slit to allow passage of the spermatic cord.

Techniques:

- Central feature is polypropylene mesh over unrepaired floor. Gilbert repair uses a cone shaped plug placed thru deep ring. Slit placed in mesh for cord structures.

Figure 21. PerFix plug (1) flower-shaped polypropylene mesh plug with multiple petals, and onlay graft with slit to accommodate the spermatic cord; Kugel Patch (2) “Race-track” oval shaped polypropylene mesh graft with pocket for insertion and larger gauge polypropylene ring to hold graft’s flat

Figure 21. PerFix plug (1) flower-shaped polypropylene mesh plug with multiple petals, and onlay graft with slit to accommodate the spermatic cord; Kugel Patch (2) “Race-track” oval shaped polypropylene mesh graft with pocket for insertion and larger gauge polypropylene ring to hold graft’s flat

shape; Prolene hernia system (3) bilayer patch repair. Bilayer polypropylene

mesh. Three-in-one device with round disc for properitoneal repair, plug effect of connector, and oblong shaped onlay component

The mesh is attached to the inguinal ligament, the coverings of the pubis, the rectus sheath and the conjoined aponeurosis and tendon. It is also fashioned by a slot laterally above and below the cord at the internal ring (Fig. 20).

The PerFix Plug repair of direct and indirect hernias is an adaptation of Gilbert’s free-formed umbrella-shaped plug, which was initially used as a plug in the internal ring for treatment of indirect inguinal hernias (Fig. 21, 1). Currently, the PerFix Plug is manufactured and placed in the internal ring and fixed with sutures to the surrounding tissues. When a direct hernia is present, the PerFix Plug is used in a similar fashion. When pantaloon or unusually large direct hernias are present, multiple plugs are sewn together to repair the defect. In addition to the plugs, an onlay patch is provided, which can be used with or without sutures over the posterior wall and around the spermatic cord lateral to the internal ring.

The Kugel patch is a polypropylene, oblong-shaped mesh with a thickened polypropylene thread that encourages the mesh to flatten. The Kugel approach is through a small incision above the internal ring. The preperitoneal space is entered and dissected free. An indirect sac is retracted or transsected, and the threshold of the internal ring is thereby freed of the peritoneal sac. The prosthesis is inserted and fixed in place with a single suture and then held in place by the natural intra-abdominal forces (Pascal’s principle) (Fig. 21, 2). In this procedure, the spermatic cord anterior to the interior ring is not handled. This approach is designed to protect the internal ring and posterior groin wall as well as the femoral canal.

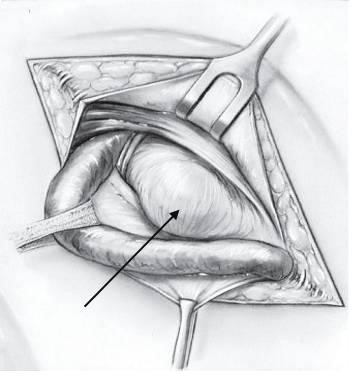

The Prolene Hernia System bilayer patch device (Fig. 21, 3) has a combined onlay graft (like a Lichtenstein repair) and underlay graft (like a Stoppa or Kugel patch); these are held together by a connector (like a plug). The external oblique aponeurosis is opened through a 5- cm groin incision, the spermatic cord is elevated, and an anterior space is created for placement of the onlay component of the device. If an indirect hernia sac is present, it is invaginated through the internal ring. If a posterior wall hernia is present (direct hernia), the defective tissue is circumscribed. In either case, the preperitoneal space (space of Bogros) is dissected free with a 4 × 4 sponge (Fig. 22).

Figure 22. Sponge dissection, posterior space.

Sponge traction in the properitoneal space is more effective in creating the space than in the gloved finger of the surgeon

The Prolene Hernia System is inserted through either of these defects. If a pantaloon hernia exists, the deep epigastric vessels are divided, and the two defects are converted to a single defect. The entire Prolene Hernia System is inserted through the posterior wall defect or internal ring. The underlay component is deployed so that the edge of the graft is at complete distraction from the connector (Fig. 23). The lateral portion of the underlay graft descends caudad to the Cooper ligament, thereby protecting the femoral canal. The onlay graft is extracted and placed against the posterior wall into the anterior space beneath the external and internal oblique muscles and laid against the transversus arch down to and over the pubic tubercle. A few sutures are placed in the onlay graft. At minimum, one is placed at the pubic tubercle, one at the mid portion of the transversus arch, and one at the mid portion of the inguinal ligament. The spermatic cord is accommodated with a central or lateral slit in the onlay component.

Figure 23. The forefinger unfurls the underlay component of the Prolene Hernia System device

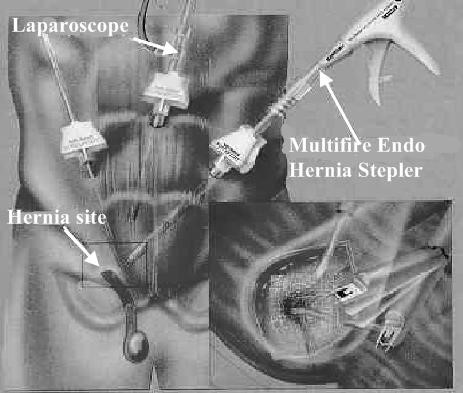

Laparoscopic hernia repair (Fig. 24):

- Early attempts resulted in exceptionally high reoccurrence rates.

- Current techniques include:

- Transabdominal preperitoneal repair (TAPP).

- Totally extraperitoneal approach (TEPA).

- Intraperitoneal onlay mesh approach (IPOM).

Figure 24. Laparoscopic mesh repair

1. Transabdominal Preperitoneal Repair (TAPP): Infraumbilical incision.

- Incise peritoneum from within abdomen.

- Direct visualization of hernia.

- Mesh placed over entire area, secured with staples or tacks. Peritoneum returned to line repair.

2. Totally Extraperitoneal Repair (TEP):

- Balloon entered into preperitoneum and inflated; creates space for scope.

- Mesh repair.

- Benefits.

- No risk of damage to peritoneal structures. No adhesive complications.

3. Intraperitoneal Onlay Mesh Approach (IPOM):

- Less popular.

- Diagnostic laproscopy.

- Mesh stapled over visible defect w/o dissection of peritoneum or establishment of defect borders.

- Quick, but high risk of adhesion of intestinal content to mesh.

Complications of herniorrhaphy: wound sepsis (especially due to faulty technique); hematoma; lymphocele (commoner after operations for femoral hernia); wound sinus (especially when foreign tissue is used for the repair); division of spermatic cord (especially in infantile hernia operation); testicular ischemia (especially after large or recurrent hernia repairs); testicular atrophy; hydrocele; nerve entrapment: pain, parasthesia or numbness; recurrence (especially after operations for large hernias in elderly males or sepsis); general: retention of urine; respiratory complications; thromboembolic complications.

Treatment of strangulated inguinal hernia. The treatment of strangulated hernia is by emergency operation. (“The danger is in the delay, not in the operation” – Astley Cooper.)

If dehydration and collapse are present, intravenous fluid replacement and gastric aspiration for 1–3 hours are invaluable. It is absolutely essential to make sure that the stomach is emptied just before commencing the anesthetic.

The passing of a large-bore stomach tube is the best way of preventing vomiting, drowning, and cardiac arrest during the induction. The bladder must also be emptied, if necessary by a catheter. SuiTable broad-spectrum antibiotics are given i.v.

Operative complications. Approximately 7 % of people undergoing surgical hernia repair will have complications.

- These are short-term and usually trea Table.

- The hernia that comes back after initial surgical repair can be repaired by the same or an alternate method.

- Complications include the following: recurrence (most common); urinary retention; wound infection; fluid build-up in scrotum (called hydrocele formation); scrotal hematoma (bruise); testicular damage on the affected side (rare).

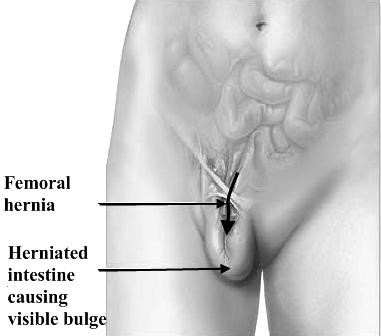

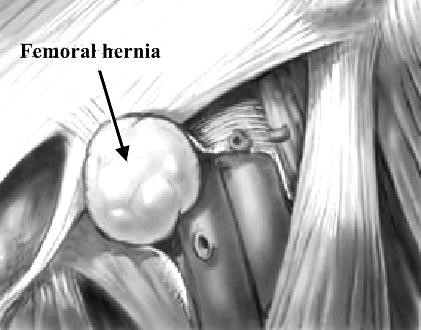

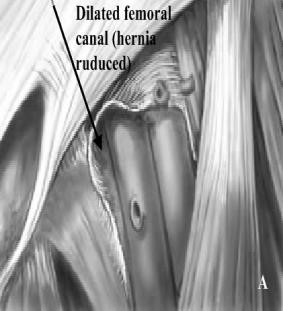

6. FEMORAL HERNIA

The femoral canal is the path through which the femoral artery, vein, and nerve leave the abdominal cavity to enter the thigh. Although normally a tight space, sometimes it becomes large enough to allow abdominal contents (usually intestine) to protrude into the canal. A femoral hernia causes a bulge just below the inguinal crease in roughly the mid-thigh area. Usually occurring in women, femoral hernias are particularly at risk of becoming irreducible (not able to be pushed back into place) and strangulated. Not all hernias that are irreducible are strangulated (have their blood supply cut off), but all hernias that are irreducible need to be evaluated by a health-care provider.

Femoral hernia is the third most common type of hernia (incisional hernia comes second). It accounts for about 20 per cent of hernias in women, and 5 per cent in men.

Surgical anatomy. The femoral canal occupies the most medial compartment of the femoral sheath, and it extends from the femoral ring above to the saphenous opening below. It is 1.25 cm long and 1.25 cm wide at its base, which is directed upwards. The femoral canal contains fat, lymphatic vessels, and the lymph node

The femoral ring is bounded:

- anteriorly by the inguinal ligament;

- posteriorly by Astley Cooper’s (iliopectineal) ligament, the pubic bone, and the fascia over the pectineus muscle;

- medially by the concave knife-like edge of Gimbernat’s (lacunar) ligament, which is also prolonged along the iliopectineal line as Astley Cooper’s ligament; laterally by a thin septum separating it from the femoral vein.

Pathology. A hernia passing down the femoral canal descends vertically as far as the saphenous opening. While it is confined to the inelastic walls of the femoral canal the hernia is necessarily narrow, but once it escapes through the saphenous opening into the loose areolar tissue of the groin, it expands, sometimes considerably. A fully distended femoral hernia assumes the shape of a retort, and its bulbous extremity may be above the inguinal ligament. By the time the contents have pursued so tortuous a path they are usually irreducible and apt to strangulate, a circumstance which is also favored by the rigidity of the surrounds of the femoral ring (Fig. 25).

Figure 25. Femoral hernia

Clinical features. Femoral hernia is rare before puberty. Between 20 and 40 years of age the prevalence rises, and continues to old age. The right side is affected twice as often as the left, and in 20 per cent of cases the condition is bilateral. The symptoms to which a femoral hernia gives rise are less pronounced than those of an inguinal hernia.

Differential diagnosis. A femoral hernia has to be distinguished from the following:

- An inguinal hernia. An inguinal hernia lies above and medial to the medial end of the inguinal ligament at its attachment to the pubic tubercle. Occasionally the fundus of a femoral hernia sac overlies the inguinal ligament.

- A saphena varix. A saphena varix is a saccular enlargement of the termination of the long saphenous vein and it is usually accompanied by other signs of varicose veins. The swelling disappears completely when the patient lies down, while a femoral hernia sac usually is still palpable.

- An enlarged femoral lymph node. If there are other enlarged lymph nodes in the region the diagnosis is tolerably simple, but when lymph node alone is affected the diagnosis may be impossible unless there is a cause, such as an infected wound or abrasion on the corresponding limb or on the perineum. Doubt should be removed by immediate surgery.

- Lipoma.

- Hydrocele of a femoral hernial sac.

Treatment. The constant risk of strangulation is sufficient reason for urging operation. A truss is contraindicated because of this risk.

Operative treatment:

The low operation (Lockwood). The sac is dissected out below the inguinal ligament via a groin-crease incision. It is essential to peel off all the anatomical layers which cover the sac. These are often thick and fatty. After dealing with the contents the neck of the sac is pulled down, ligated as high as possible and allowed to retract through the femoral canal. The canal is closed by suturing the inguinal ligament to the iliopectineal line using unabsorbable sutures.

The high (McEvedy) operation. A vertical incision is made over the femoral canal and continued upwards above the inguinal ligament. Through the lower part of the incision the sac is dissected out. The upper part of the incision exposes the inguinal ligament and the rectus sheath. The superficial inguinal ring is identified, and an incision 2.5 cm above the ring and parallel to the outer border of the rectus muscle is deepened until the extraperitoneal space is found. By gauze dissection in this space the hernial sac entering the femoral canal can be easily identified. Should the sac be empty and small, it can, be drawn upwards; if it is large, the fundus is opened below, and its contents, if any, dealt with appropriately before delivering the sac upwards from its canal. The sac is then freed from the extraperitoneal tissue and its neck is ligated. An excellent view of the iliopectineal ligament is obtained and the conjoined tendon is sutured to it with non-absorbable sutures.

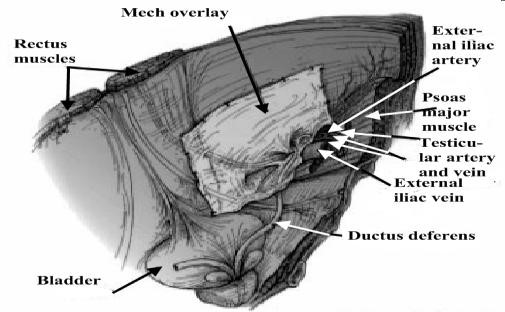

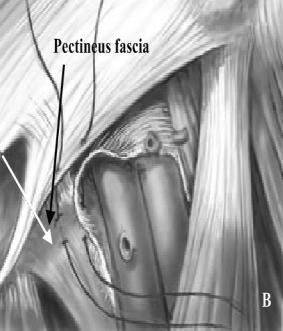

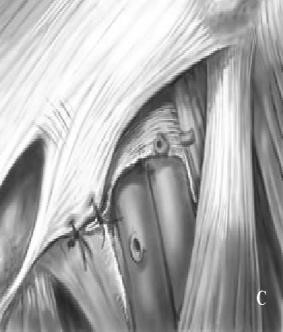

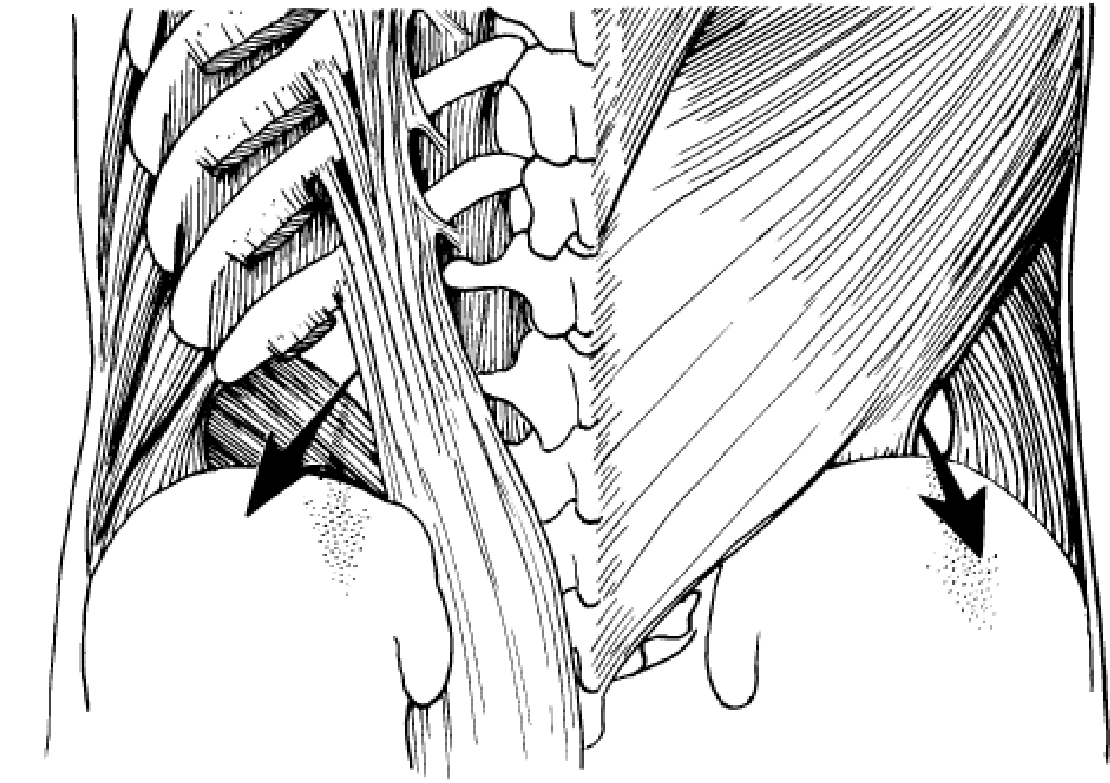

Bassini Repair (Fig. 26).

Original approach was inferior to inguinal ligament with excision of sac and closure of inguinal ligament to pectineal fascia and Cooper’s ligament from below. Hernia is approached via inguinal incision and Coopers Ligament repair performed. Transverse incision 4 cm above pubic tubercle. Expose the Femoral ring preperitonealy. Coopers ligament sutured to ileopubic tract.

Figure 26. Bassini repair

7. UMBILICAL HERNIA

These common hernias (10–30%) are often noted at birth as a protrusion at the bellybutton (the umbilicus). This is caused when an opening in the abdominal wall, which normally closes before birth, doesn’t close completely (Fig. 27). If small (less than half an inch), this type of hernia usually closes gradually by age 2. Larger hernias and those that do not close by themselves usually require surgery at age 2–4 years. Even if the area is closed at birth, umbilical hernias can appear later in life because this spot may remain a weaker place in the abdominal wall. Umbilical hernias can appear later in life or in women who are pregnant or who have given birth (due to the added stress on the area). This is a hernia through a weak umbilical scar. The ratio of males to females is 2 : 1.

These common hernias (10–30%) are often noted at birth as a protrusion at the bellybutton (the umbilicus). This is caused when an opening in the abdominal wall, which normally closes before birth, doesn’t close completely (Fig. 27). If small (less than half an inch), this type of hernia usually closes gradually by age 2. Larger hernias and those that do not close by themselves usually require surgery at age 2–4 years. Even if the area is closed at birth, umbilical hernias can appear later in life because this spot may remain a weaker place in the abdominal wall. Umbilical hernias can appear later in life or in women who are pregnant or who have given birth (due to the added stress on the area). This is a hernia through a weak umbilical scar. The ratio of males to females is 2 : 1.

Most do not become obvious until the infant is several weeks old. The hernia

Figure 27. Umbilical hernia is often symptomless, but increase in the size of the hernia on crying causes pain, which makes the infant cry the more. Small hernias are spherical; those that increase in size tend to assume a conical shape and are present apart from crying. Obstruction or strangulation below the age of three years is extremely uncommon.

Treatment. Conservative treatment by masterly inactivity is successful in about 93 per cent of cases. When the hernia is symptomless, reassurances of the parents is all that is necessary, for in a very high percentage of cases the hernia will be found to disappear spontaneously during the first few months of life.

Herniorrhaphy. In cases where masterly inactivity fails, operation is required, and it should be carried out, preferably, about the age of 2 years.

Mayo’s Operation. A transverse elliptical incision is made around the umbilicus. The subcutaneous tissues are dissected off the rectus sheath to expose the neck of the sac. The neck is incised to expose the contents. Intestine is returned to the abdomen. Any adherent omentum is freed, and ligated by transfixion if it is bleeding. Excess adherent omentum can be removed with the sac if necessary. The sac is then removed and the peritoneum of the neck closed with catgut. The aponeurosis on both sides of the umbilical ring is incised transversely for 2.5 cm or more sufficiently to allow an overlap of 5 to 6cm. Three to five mattress sutures of fine, unabsorbable material are then inserted into the aponeurosis. If the patient has a tendency to bronchitis, it is wise to prescribe antibiotic therapy and breathing exercises.

8. LUMBAR HERNIA

There are three types of lumbar hernia (Fig. 28). The first two are primary lumbar hernia which come out through the superior lumbar triangle and the inferior lumbar triangle. The 3rd one is an acquired lumbar hernia and is better called an incisional lumbar hernia.

Figure 28. Lumbar hernia

Superior lumbar hernia. This is rarer than the inferior lumbar hernia. Superior lumbar hernia is protrusion of abdominal contents through the superior lumbar triangle, which is bounded above by the 12th rib, medially by the sacrospinalis and laterally by the posterior border of the obliquus internus abdominis.

Inferior lumbar hernia is more common than the superior one and the hernia protrudes through the inferior lumbar triangle or lumbar triangle of Petit. This triangle is bounded below by the crest of the ilium, medially by the anterior border of the latissimus dorsi and laterally by the posterior border of the obliquus externus abdominis.

Incisional lumbar hernia may occur in the lumbar region (a) following an operation or an infected kidney or drainage of lumbar abscess, in which the wound gets infected post-operatively or (b) following paralysis of the muscles of the lumbar region either due to injury of the nerve supplying this region or due to poliomyelitis. This is also known as phantom hernia.

Clinical features. Patient complains of a swelling in the typical lumbar region.

On examination there is soft swelling which corresponds to the superior or inferior lumbar triangle. The swelling is reducible. It may be reduced by itself when the patient lies down. Impulse on coughing is also present.

Differential diagnosis. When there is reducibility and impulse on coughing diagnosis may not be difficult, yet the following conditions should be kept in mind.

- Lipoma. It is a firm or soft swelling, which moves easily over the taut muscles. It is not reducible and there is no impulse on coughing. On moving the swelling one will see puckering of the skin.

- Cold abscess pointing to this region. Paravertebral cold abscess may become superficial through the lumbar triangle. This condition very much mimics lumbar hernia. It gives rise to a soft cystic swelling. Fluctuation test is positive. This swelling is not reducible. But cough impulse may be present.

X-ray of the thoracic and lumbar spine is confirmatory.

- Phantom hernia due to local muscular paralysis – discussed above.

Treatment. Primary lumbar hernia is treated by herniotomy and repair of the gap i.e. hemiorrhaphy.

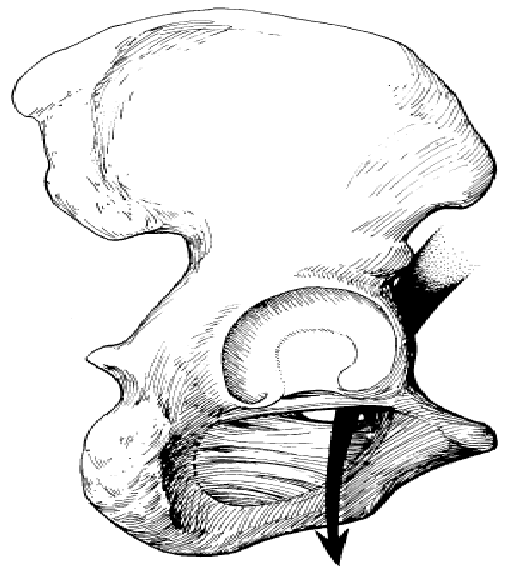

9. OBTURATOR HERNIA

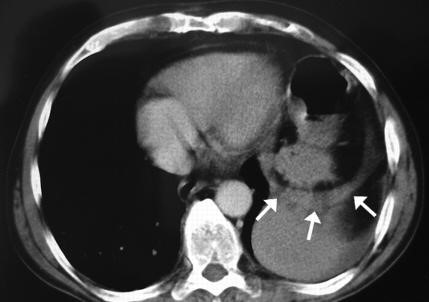

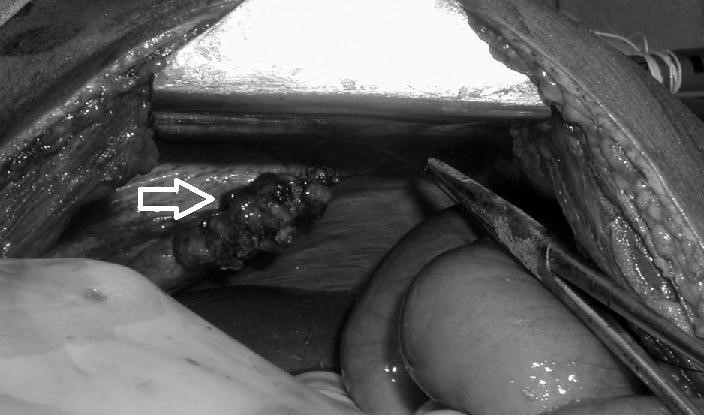

This extremely rare abdominal hernia develops mostly in women. This hernia protrudes from the pelvic cavity through an opening in the pelvic bone (obturator foramen). This will not show any bulge but can act like a bowel obstruction and cause nausea and vomiting. Because of the lack of visible bulging, this hernia is very difficult to diagnose. It means hernia occurs through the obturator foramen traversed by the obturator vessels and nerve. This obturator foramen is

This extremely rare abdominal hernia develops mostly in women. This hernia protrudes from the pelvic cavity through an opening in the pelvic bone (obturator foramen). This will not show any bulge but can act like a bowel obstruction and cause nausea and vomiting. Because of the lack of visible bulging, this hernia is very difficult to diagnose. It means hernia occurs through the obturator foramen traversed by the obturator vessels and nerve. This obturator foramen is

wider in females and that is why it is about

6 times commoner in women (Fig. 29). Figure 29. Obturator hernia

It is a condition of:

- Rare form of hernia.

- Protrusion of intra-abdominal contents through obturator foramen.

- Female/male ratio 6:1.

- The obturator foramen is formed by the ischial and pubic rami.

- Obturator vessels and nerve lie posterolateral to the hernia sac in the canal.

- Small bowel is the most likely intraabdominal organ to be found in an obturator hernia.

Clinical features. Most of the patients are old women above 60 years of age who have lost considerable fat.

The condition is difficult to diagnose, since the swelling is covered by the pectineus and no definite swelling can be seen even in the Scarpa’s triangle. The hernia becomes only apparent when the limb is flexed, abducted and rotated outwards. The patient usually keeps the limb in the semiflexed position and movements increase pain.

Obturator hernia often gets strangulated as it comes out through an opening surrounded by osseoaponeurosis. In about half of the cases of strangulation, pain is referred along the obturator nerve to the knee joint of the corresponding side by its articulate branch.

Only rectal or vaginal examination can detect the tender swelling in the region of the obturator foramen.

Richter’s hernia is quite common.

Treatment. Operation should always be performed as strangulation is very common.

Abdominal approach is usually preferred by lower paramedian incision as the condition is often discovered only after laparotomy which has been performed for intestinal obstruction. The obturator foramen is widened and the hernia is pulled in after the abdomen has been properly mopped to prevent contamination from the toxic fluid of the hernial sac. The obturator vessels are always vulnerable of being injured. If the hernia cannot be released from the abdomen or the diagnosis has been made before operation, the femoral approach may be employed.

Femoral approach. A vertical incision is made extending downwards from the inguinal ligament 2cm medial to the femoral vessels. The adductor longus is retracted medially. The pectineus muscle is separated or divided to expose the obturator externus. The hernial sac is usually found lying on the surface of this muscle having emerged along its superior border. The sac and the contents are dealt with in the similar manner as strangulated hernia and hemiorrhaphy is performed by repairing the gap in the obturator foramen.

10. OTHER UNIMPORTENT RARE HERNIA

Epigastric hernia. Occurring between the navel and the lower part of the rib cage in the midline of the abdomen, epigastric hernias are composed usually of fatty tissue and rarely contain intestine. Formed in an area of relative weakness of the abdominal wall, these hernias are often painless and unable to be pushed back into the abdomen when first discovered.

Gluteal hernia. This hernia extrudes out through the greater sciatic foramen either above or below the piriformis muscle.

Sciatic hernia. This hernia occurs through the lesser sciatic foramen. In the differential diagnosis of gluteal and sciatic herniae one should remember a cold abscess, a lipoma, a gluteal aneurysm, fibrosarcoma beneath the gluteus maximus.

Spigelian hernia. It is a type of interparietal hernia occurring at the level of the arcuate line just lateral to the rectus muscle (Fig. 30).

The extraperitoneal fat along with the hernial sac lies just deep to the internal oblique muscle or may advance to reach the gap between the external and internal oblique muscles. Only a slight swelling can be detected.

The extraperitoneal fat along with the hernial sac lies just deep to the internal oblique muscle or may advance to reach the gap between the external and internal oblique muscles. Only a slight swelling can be detected.

Treatment. Operation is the treatment. Incision is made on the swelling just lateral to the rectus muscle. After incision of skin and subcutaneous tissue, external aponeurosis is split to expose the hemial sac. The sac is isolated, the contents reduced. The sac is ligated and excised.

The transversus and oblique muscles are repaired. Figure 30.

Perineal hernia. In this case hernia occurs Spigelian hernia (arrow) through the pelvic floor. It is extremely rare and occasionally seen in:

- Postoperative hernia through the perineal scar following excision of rectum.

- Pudenda hernia when the hernia occurs as a swelling of the labium majus.

- Ischiorectal hernia, in which the hernia passes through the levator ani into the ischiorectal fossa through hiatus of Schwalbe.

11. INCISIONAL HERNIA

Abdominal surgery causes a flaw in the abdominal wall. This flaw can create an area of weakness in which a hernia may develop. This occurs after 2–10 % of all abdominal surgeries, although some people are more at risk.

Even after surgical repair, incisional hernias may return.

An incisional hernia (synonyms:

ventral hernia or postoperative hernia) is one which occurs through an acquired scar in the abdominal wall caused by a previous surgical operation or an accidental trauma.

Scar tissue is inelastic and can be stretched forcibly if subjected to constant strain. When a ventral hernia occurs, it usually arises in the abdominal wall where a previous surgical incision was made. A hernia involves the weakening of a patient’s abdominal muscles, resulting in a bulge or tear (Fig. 31). Figure 31. Postoperative hernia

Etiology

1. Defect of the patient:

- Obese individuals with lax muscles.

- Patients suffering from chronic cough, which may continue in the early postoperative period and will lead to incisional hernia.

- Undue abdominal distension in the early postoperative period.

- Malnutrition – patients with severe anemia, hypoproteinaemia or Vitamin С deficiency may predispose to incisional hernia.

2. Fault during operation:

- Injury to the motor nerves supplying the area. Certain incisions are vulnerable to cause nerve injury e.g. Kocher’s subcostal incision for cholecystectomy often inflicts injury to the 8th, 9th and 10th intercostal nerves; Battle’s pararectal incision for appendicectomy; McBurney’s incision for appendicectomy may injure the subcostal or ilioinguinal nerve.

- Particular care was not taken during closure of the wound particularly the deeper layers.

- Haemostasis was not perfect or the tissues were manhandled, so that early postoperative infection was the result.

- Tube drainage through the laparotomy wound.

- Certain incisions are more liable to cause incisional hernia e.g. midline infraumbilical incision for caesarean section.

3. Postoperative causes.

- Infection. This seems to be the commonest cause.

- Postoperative cough and distension.

- Postoperative peritonitis due to more chance of wound infection.

- Too early removal of sutures.

- Steroid therapy in the postoperative period.

- Pathology.

Often the incisional hernia starts unnoticed and symptomless with partial disruption of the deeper layers of a laparotomy wound during very early postoperative period. So careful closure of the wound is extremely important to prevent incisional hernia.

Wound infection often causes disruption of sutures thus the muscles are separated by weak scar tissue. A portion of the muscles may also be destroyed by infections which are resolved afterwards by fibrosis. This also causes weak scar. Incisional hernia occurs through this weak scar.

SWR (Situation, wide, recurrence) classification of incisional hernia 1. Localization (S):

- median (М): М1 – supraumdilical hernia; М2 – periumbilical hernia; М3 – subumbilical hernia; М4 – pubic hernia.

- lateral (L): L1 – subcostal hernia; L2 – transversal hernia; L3 – inguinal hernia; L4 – lumbar hernia.

2. The Width of hernia port (W): W1 – till 5cm; W2 – 5–10 cm; W3 – 10–15 cm; W4 – more than 15 cm.

3. Relapses (R): R – no relapse; R1 – first relapse; R2 – second relapse etc.

Clinical features

A previous operation or a trauma is often noticed. Patient may give a history of wound infection. Incisional hernia may occur at any age, but more common in fatty elderly females.

The commonest symptoms are the swelling and the pain. Sometimes attacks of subacute intestinal obstruction may occur; leading to abdominal colic, vomiting, constipation and distension of the abdomen. Strangulation, though uncommon, is liable to occur at the neck of a small sac or in a locule of a large hernia.

On examination the old scar is seen with the swelling. The hernia may occur through a small portion of the scar often the lower end. Often a diffuse bulge may occur involving the whole length of the scar. Usually the swelling is reducible and an expansile cough impulse is present. The defect in the abdominal wall is often palpable.

It may so happen that the hernia is irreducible. Such cases become difficult to diagnose. These cases must be differentiated with (differential diagnosis):

- A deposit of tumor.

- An old abscess.

- A hematoma.

- A foreign body granuloma.

Treatment

A few preoperative measures should be carefully adopted to lessen the chance of incisional hernia. These are:

- If the patient is obese, weight should be reduced by dieting if an elective operation has to be performed.

- If the patient has a tendency of chronic bronchitis, it should be treated first.

- During operation one must be very careful in closure of the abdomen. Deeper layers must be sutured with due respect.

- All precautions should be adopted to prevent immediate postoperative wound infection.

Operation

Ventral hernias can be repaired by the following techniques: an “open” method or a laparoscopic minimally invasive procedure. Like other hernias, a ventral hernia may become worse if left untreated. Moreover, ventral hernias can be dangerous, because abdominal structures, such as the intestines, can become stuck or twisted in the hernia, leading to a more complex and riskier operation. The only known treatment is to have the ventral hernia repaired through surgery. Any continuous or severe discomfort, redness, nausea, or vomiting resulting from the bulge associated with a hernia; are signs the hernia may be entrapped or strangulated.

The incision is deepened to the aponeurosis. The unhealthy skin is gradually dissected off the sac, which is nothing but a redundancy of peritoneum. The sac is not opened. If the sac is loculated and very adherent it is better to open the sac around its neck. The contents are freed. Adherent omentum may be ligated and removed along with the sac. Any adhesions involving the bowel should be separated as far as practicable before the hernial contents are returned to the abdomen. Repair of the hernia depends on the type of hernia and its size.

Mesh closures. These are becoming increasingly popular. The incision and the sac are dealt with similarly as done in the previous operations. The deficiency in the abdominal wall is easily made good without tension by laying and stitching a sheet a Mesh made of Dacron or polypropylene to the surrounding aponeurosis. Repair with synthetic mesh is only advised when the defect is very large and cannot be closed effectively by autogenous tissue. It cannot be used routinely as there is increased chance of infection. Collection of oozing fluid inside the wound acts as a good nidus of infection. The following points should be considered whenever a synthetic mesh is used:

- Asepsis should be maintained at all costs.

- Too much handling of the tissues should be minimized.

- Haemostasis must be carefully maintained.

- Even the pre-sterilized mesh should be handled as little as possible.

- The mesh should be placed as deeply as possible. It should be used as an onlay on the sutured peritoneum. Under no circumstance should the intestine be allowed to come in contact with the mesh lest dense adhesions should form. The mesh should not be used just under the skin.

- The mesh should be sutured all round with fine prolene sutures.

- A suction drainage should always be used to aspirate the oozing fluid and, thus, to prevent infection.

- Early ambulation is not encouraged, but movements of the legs and exercises of the legs are encouraged.

- Patient must not resume work or strenuous exercise for 6 months.

A minimally invasive laparoscopic surgical technique includes small, dime-sized incisions that allow the use of a miniature camera, or videoscope, and specialized instruments to perform the procedure. The procedure will avoid a conventional incision. The main advantages of a laparoscopic ventral hernia procedure over open surgery include:

- Less time in hospital.

- Smaller incisions.

- Less recovery time – a traditional open procedure may take approximately three to four weeks of recovery compared to one to two weeks if performed laparoscopically.

Risks and complications. All surgical procedures have risks. The risk for serious complications depends on a patient’s medical condition and age, as well as their surgeon’s and anesthesiologist’s experience. Patients should ask their doctor or surgeon about what to expect after surgery, as well as the risks that may occur with any surgery, including:

Risks of any surgery:

- Reactions to medications or anesthesia.

- Breathing problems.

- Bleeding.

- Infection.

- Injury to blood vessels.

- Injury to internal organs.

- Blood clots in the veins or lungs.

- Death (rare).

- If the surgeon uses a special mesh, or screen, to help repair the hernia, an added potential complication can be infection in the mesh. If this happens, the mesh may need to be removed or replaced.

- For patients undergoing surgical repair on a hernia that has reoccurred, there is a greater chance that the hernia will reoccur again.

Risks of conventional surgery. Additionally, conventional surgery for Ventral hernia repair has a greater potential for:

- Muscle injury.

- Recurrence of the hernia.

INTERNAL ABDOMINAL HERNIA

Higher in the abdomen, an (internal) “diaphragmatic hernia” results when part of the stomach or intestine protrudes into the chest cavity through a defect in the diaphragm. A hiatus hernia is a particular variant of this type, in which the normal passageway through which the esophagus meets the stomach

(esophageal hiatus) serves as a functional “defect”, allowing part of the stomach to (periodically) “herniate” into the chest. Hiatus hernias may be either “sliding”, in which the gastroesophageal junction itself slides through the defect into the chest, or non-sliding (also known as paraesophageal), in which case the junction remains fixed while another portion of the stomach moves up through the defect. Non-sliding or paraesophageal hernias can be dangerous as they may allow the stomach to rotate and obstruct. Repair is usually advised. A congenital diaphragmatic hernia is a distinct problem, occurring in up to 1 in 2 000 births, and requiring pediatric surgery. Intestinal organs may herniate through several parts of the diaphragm, posterolateral (in Bochdalek’s triangle, resulting in Bochdale’’s hernia), or anteromedial-retrosternal (in the cleft of Larrey/Morgagni’s foramen, resulting in Morgagni-Larrey hernia, or Morgagni’s hernia).

12. HIATAL HERNIA

A hiatal hernia is an anatomical abnormality in which part of the stomach protrudes through the diaphragm and up into the chest. Although hiatal hernias are present in approximately 15 % of the population, they are associated with symptoms in only a minority of those afflicted.

Normally, the esophagus or food tube passes down through the chest, crosses the diaphragm, and enters the abdomen through a hole in the diaphragm called the esophageal hiatus. Just below the diaphragm, the esophagus joins the stomach. In individuals with hiatal hernias, the opening of the esophageal hiatus (hiatal opening) is larger than normal, and a portion of the upper stomach slips up or passes (herniates) through the hiatus and into the chest. Although hiatal hernias are occasionally seen in infants where they probably have been present from birth, most hiatal hernias in adults are believed to have developed over many years.

Allocate:

- Sliding hiatal hernia (90 % of cases).

- Rolling hiatal hernia (paraesophageal).

Sliding hiatal hernia, the most common type of hernia, are those in which the junction of the esophagus and stomach, referred to as the gastro-esophageal junction, and part of the stomach protrude into the chest (Fig. 32). The junction may reside permanently in the chest, but often it juts into the chest only during a swallow. This occurs because with each swallow the muscle of the esophagus contracts causing the esophagus to shorten and to pull up the stomach. When the swallow is finished, the herniated part of the stomach falls back into the abdomen.

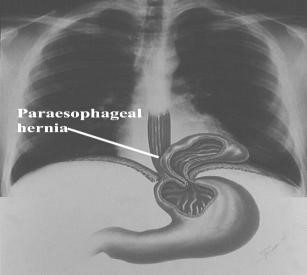

Paraesophageal hiatal hernia. Paraesophageal hernias are hernias in which the gastro-esophageal junction stays where it belongs (attached at the level of the diaphragm), but part of the stomach passes or bulges into the chest beside the esophagus. The paraesophageal hernias themselves remain in the chest at all times and are not affected by swallows (Fig. 33). A paraesophageal hiatal hernia that is large, particularly if it compresses the adjacent esophagus, may impede the passage of food into the stomach and cause food to stick in the esophagus after it is swallowed. Ulcers also may form in the herniated stomach due to the trauma caused by food that is stuck or acid from the stomach. Fortunately, large paraesophageal hernias are uncommon.

Figure 32. Sliding hiatal hiernia Figure 33. Rolling hiatal hiernia

Complications: slow bleeding, anemia, pulmonary aspiration.

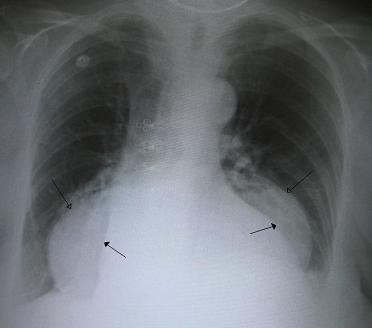

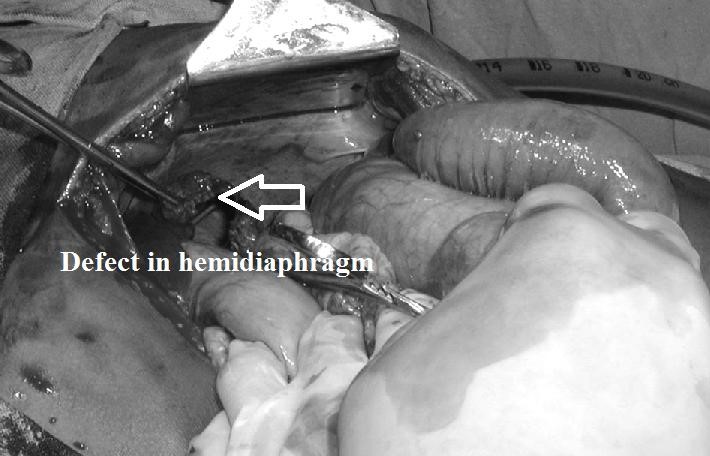

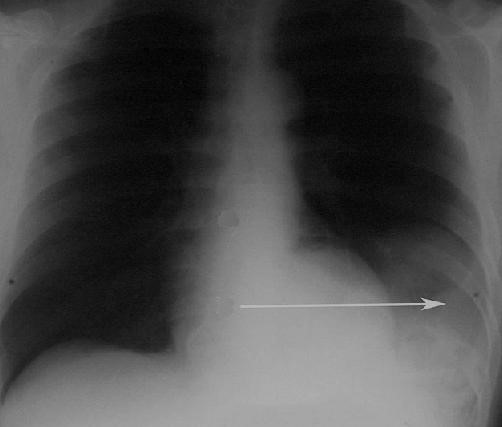

Diagnostic tools:

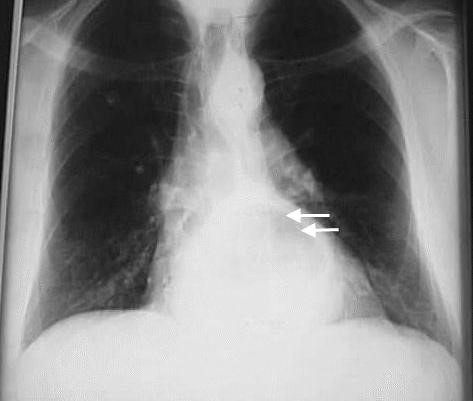

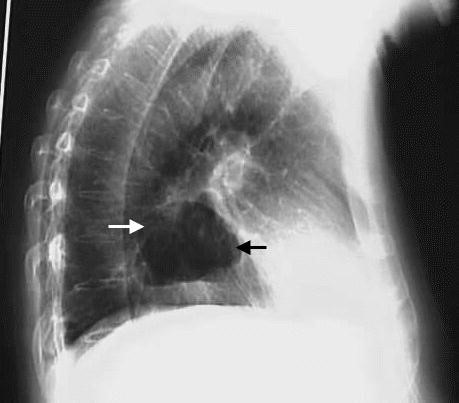

- X-ray and barium swallow (Fig. 34, 35).

- Upper endoscopy.

- Esophageal manometry.

- 24-hour ambulatory esophageal pH.

- Gastric emptying study.

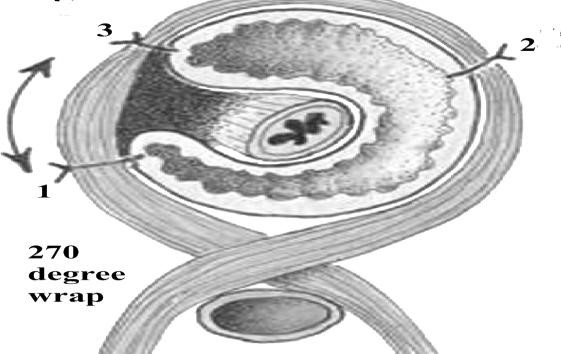

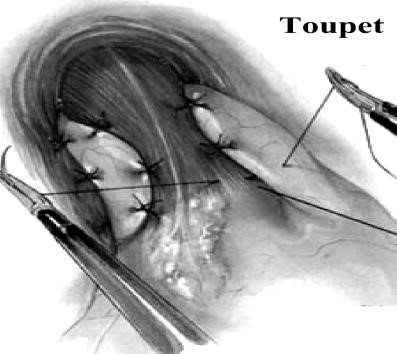

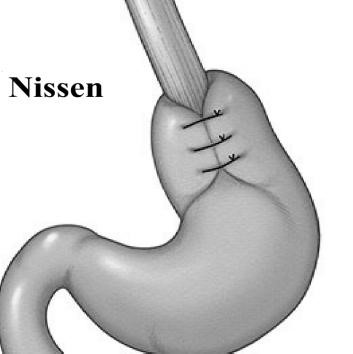

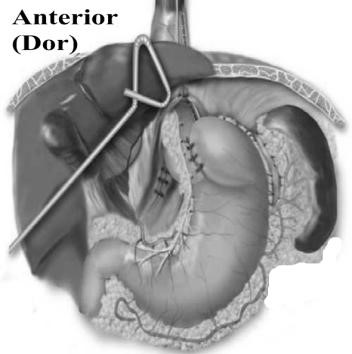

Figure 34 A large hiatus hernia on X – ray marked by open arrows in contrast to the heart borders marked by closed arrows